Natural language processing, also known as NLP, combines computer science and linguistics to understand and process the relationships contained within communication languages. Words, characters, documents, sentences, and punctuation can play a factor in how humans understand language, and using this information, computers are capable of also learning and understanding how humans communicate by analyzing these factors.

In the data science/machine learning field, preprocessing data is said to take 80-90% of the time spent on a project. Thorough preprocessing can make or break a model.

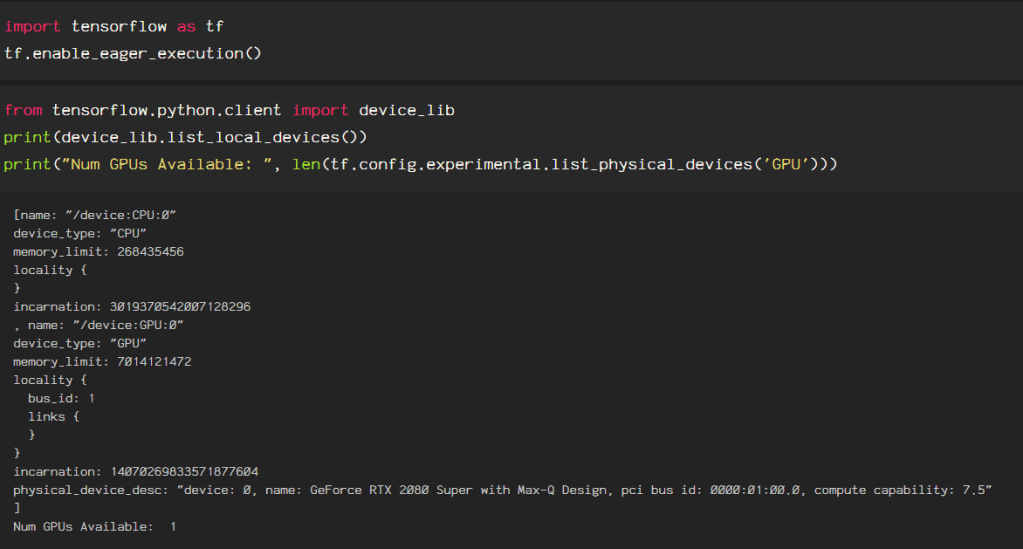

I am going to use the “Disaster Tweets” dataset from Kaggle, which can be found here. There are a multitude of packages that can be used to make this easier, such as spaCy and NLTK. For this example, I will be using regular expressions and NLTK.

Start by loading the csv file with the following line of code:

df = pd.read_csv('train.csv')

For now, I am only going to focus on the “text” column, which contains the tweet text. There are non-ascii characters, digits, upper and lowercases, hashtags, and handles to deal with, and that’s just the beginning. First, I am adding a single whitespace at the start of the tweet text, which will be explained later. Next, I remove the duplicate tweets from the dataset.

df['text'] = " " + df.text

df.drop_duplicates(subset=['text'], inplace=True)

The reason I added the whitespace at the head of each tweet is so I can expand contractions and abbreviations using a dictionary I created for this purpose. The dictionary appears as follows:

contractions_dict = {

" aint": " are not",

" arent": " are not",

" cant": " can not",

" cause": " because",

" couldve": " could have",

" couldnt": " could not",

" didnt": " did not",

" doesnt": " does not",

" dont": " do not",

" hadnt": " had not",

" hasnt": " has not",

" havent": " have not",

" hed": " he would",

" hes": " he is",

" howd": " how did",

" howdy": " how do you",

" howll": " how will",

" hows": " how is",

" id": " i would",

" ida": " i would have",

" im": " i am",

" ive": " i have",

" isnt": " is not",

" itd": " it had",

" itll": " it will",

" its": " it is",

" lets": " let us",

" maam": " madam",

" mightve": " might have",

" mighta": " might have",

" mightnt": " might not",

" mustve": " must have",

" musta": " must have",

" mustnt": " must not",

" neednt": " need not",

" oclock": " of the clock",

" shes": " she is",

" shoulda": " should have",

" shouldve": " should have",

" shouldnt": " should not",

" so'd": " so did",

" thatd": " that would",

" thats": " that is",

" thered": " there had",

" theres": " there is",

" theyd": " they would",

" theyda": " they would have",

" theyll": " they will",

" theyre": " they are",

" theyve": " they have",

" wasnt": " was not",

" weve": " we have",

" werent": " were not",

" whatll": " what will",

" whatllve": " what will have",

" whatre": " what are",

" whats": " what is",

" whatve": " what have",

" whens": " when is",

" whenve": " when have",

" whered": " where did",

" whers": " where is",

" whereve": " where have",

" wholl": " who will",

" whollve": " who will have",

" whos": " who is",

" whove": " who have",

" whys": " why is",

" whyve": " why have",

" willve": " will have",

" wont": " will not",

" wontve": " will not have",

" wouldve": " would have",

" wouldnt": " would not",

" wouldntve": " would not have",

" yall": " you all",

" yalls": " you alls",

" yalld": " you all would",

" yalldve": " you all would have",

" yallre": " you all are",

" yallve": " you all have",

" youd": " you had",

" youda": " you would have",

" youdve": " you would have",

" youll": " you you will",

" youllve": " you you will have",

" youre": " you are",

" youve": " you have",

" ain't": " are not",

" aren't": " are not",

" can't": " can not",

" can't've": " can not have",

" 'cause": " because",

" bc": " because",

" b/c": " because",

" could've": " could have",

" couldn't": " could not",

" couldn't've": " could not have",

" didn't": " did not",

" doesn't": " does not",

" don't": " do not",

" hadn't": " had not",

" hadn't've": " had not have",

" hasn't": " has not",

" haven't": " have not",

" he'd": " he would",

" he'd've": " he would have",

" he'll": " he will",

" he'll've": " he will have",

" he's": " he is",

" how'd": " how did",

" how'd'y": " how do you",

" how'll": " how will",

" how's": " how is",

" i'd": " i would",

" i'd've": " i would have",

" i'll": " i will",

" i'll've": " i will have",

" i'm": " i am",

" i've": " i have",

" isn't": " is not",

" it'd": " it had",

" it'd've": " it would have",

" it'll": " it will",

" it'll've": " it will have",

" it's": " it is",

" let's": " let us",

" ma'am": " madam",

" mayn't": " may not",

" might've": " might have",

" mightn't": " might not",

" mightn't've": " might not have",

" must've": " must have",

" mustn't": " must not",

" mustn't've": " must not have",

" needn't": " need not",

" needn't've": " need not have",

" o'clock": " of the clock",

" oughtn't": " ought not",

" oughtn't've": " ought not have",

" shan't": " shall not",

" sha'n't": " shall not",

" shan't've": " shall not have",

" she'd": " she would",

" she'd've": " she would have",

" she'll": " she will",

" she'll've": " she will have",

" she's": " she is",

" should've": " should have",

" shouldn't": " should not",

" shouldn't've": " should not have",

" so've": " so have",

" so's": " so is",

" that'd": " that would",

" that'd've": " that would have",

" that's": " that is",

" there'd": " there had",

" there'd've": " there would have",

" there's": " there is",

" they'd": " they would",

" they'd've": " they would have",

" they'll": " they will",

" they'll've": " they will have",

" they're": " they are",

" they've": " they have",

" to've": " to have",

" wasn't": " was not",

" we'd": " we had",

" we'd've": " we would have",

" we'll": " we will",

" we'll've": " we will have",

" we're": " we are",

" we've": " we have",

" weren't": " were not",

" what'll": " what will",

" what'll've": " what will have",

" what're": " what are",

" what's": " what is",

" what've": " what have",

" when's": " when is",

" when've": " when have",

" where'd": " where did",

" where's": " where is",

" where've": " where have",

" who'll": " who will",

" who'll've": " who will have",

" who's": " who is",

" who've": " who have",

" why's": " why is",

" why've": " why have",

" will've": " will have",

" won't": " will not",

" won't've": " will not have",

" would've": " would have",

" wouldn't": " would not",

" wouldn't've": " would not have",

" y'all": " you all",

" y'alls": " you alls",

" y'all'd": " you all would",

" y'all'd've": " you all would have",

" y'all're": " you all are",

" y'all've": " you all have",

" you'd": " you had",

" you'da": " you would have",

" you'd've": " you would have",

" you'll": " you you will",

" you'll've": " you you will have",

" you're": " you are",

" you've": " you have",

" hwy": " highway",

" fvck": " fuck",

" im": " i am",

" rt": " retweet",

" fyi": " for your information",

" omw": " on my way",

" 1st": " first",

" 2nd": " second",

" 3rd": " third",

" 4th": " fourth",

" u ": " you ",

" r ": " are ",

}

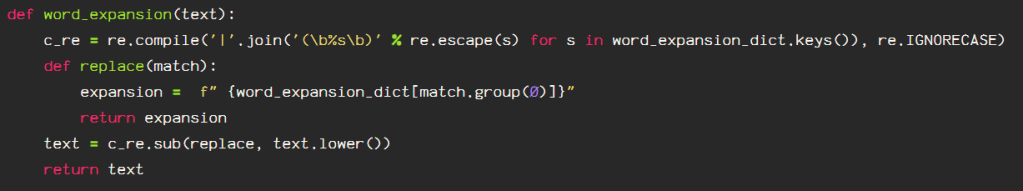

There are other options, for instance, removing the punctuation before processing the contractions will allow for a shorter dictionary, however, when the punctuation is removed, sometimes, these contractions end up being a completely different word. An example of this is “she’ll”, which would become “shell”, and these words have completely different meanings. So I process the expansion before cleaning the punctuation from the text so that the word meaning is not lost, as that is the entire point of NLP. Using the following function, I use regex to compile the dictionary keys, then I match the contraction to the correlating expansion phrase or word, then follow up with the regex ‘sub’ function, returning the text replacing the contraction.

def expand_contractions(text, c_re=c_re):

c_re = re.compile('|'.join('(%s)' % k for k in contractions_dict.keys()))

def replace(match):

expansion = f" {contractions_dict[match.group(0)]}"

return expansion

text = c_re.sub(replace, text.lower())

return text

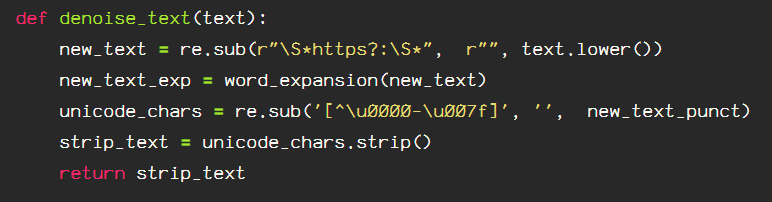

Next, I will remove the ‘noise’ from the text. Noise includes emojis, punctuation, and URLs. I am also running the contraction expansion function in this block of self explanatory code:

def denoise_text(text):

new_text = re.sub(r"\S*https?:\S*", r"", text.lower())

new_text_contractions = expand_contractions(new_text)

new_text_punct = re.sub(r"[^\w\s@#]", r"", new_text_contractions)

new_text_ascii = re.sub('[^\u0000-\u007f]', '', new_text_punct)

text = new_text_ascii.strip()

return text

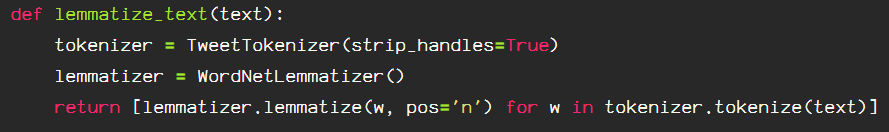

After denoising the tweets, I will tokenize and lemmatize the text using NLTK’s TweetTokenizer() and WordNetLemmatizer(). With the TweetTokenizer(), NLTK provides a quick and accesible way to remove the twitter handles, and reduce the length. Reduce_len is an optional argument, but I use it due to the way people use language in tweets, for example, “waaaaay” becomes “waaay”, or “waaaay” becomes “waaay”, providing a uniform baseline for the exaggerated words.

def lemmatize_text(text):

tokenizer = TweetTokenizer(strip_handles=True, reduce_len=True)

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

return [lemmatizer.lemmatize(w, pos='v') for w in tokenizer.tokenize(text)]

There are several instances of digits in the tweets provided, and I am going to expand these digits to words using inflect. Instructions for installation can be found here.

def replace_numbers(tokens):

# replace integers with string formatted words for numbers

dig2word = inflect.engine()

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

if word.isdigit():

new_word = dig2word.number_to_words(word)

new_tokens.append(new_word)

else:

new_tokens.append(word)

return new_tokens

I will also remove the non-ASCII characters from the tokens like so:

def remove_non_ascii(tokens):

# remove non ascii characters from text

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

new_token = unicodedata.normalize('NFKD', word).encode('ascii', 'ignore').decode('utf-8', 'ignore')

new_tokens.append(new_token)

return new_tokens

I will be removing the “stopwords” from the tweets as well, using NLTK’s stopwords list, which is available in multiple languages. It removes common words that can occur too frequently to allow any information to be obtained from their use.

def remove_stopwords(tokens):

stop_list = stopwords.words('english')

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

if word not in stop_list:

new_tokens.append(word)

return new_tokens

Next, I will create a wrapper to normalize the tokens combining the processing methods.

def norm_text(tokens):

words = replace_numbers(tokens)

tokens = remove_stopwords(words)

return tokens

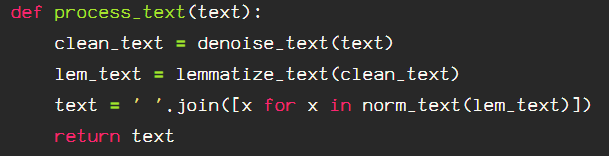

I am able to join all of the above processing techniques in the following function:

def process_text(text):

clean_text = denoise_text(text)

lem_text = lemmatize_text(clean_text)

text = ' '.join([x for x in norm_text(lem_text)])

text = re.sub(r"-", r" ", text)

return text

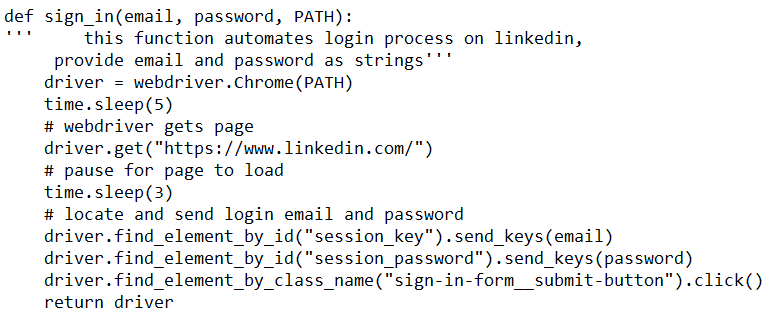

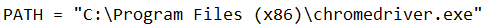

To utilize these in a simple manner, I will combine these and run them on the “text” dataframe column.

def tweet_preprocess(df):

"""

combine regex and nltk processing for tweet text processing.

includes contractions dictionary, stemming option, just replace

lemmatize tokenizer with the stemming function.

"""

contractions_dict = {

" aint": " are not",

" arent": " are not",

" cant": " can not",

" cause": " because",

" couldve": " could have",

" couldnt": " could not",

" didnt": " did not",

" doesnt": " does not",

" dont": " do not",

" hadnt": " had not",

" hasnt": " has not",

" havent": " have not",

" hed": " he would",

" hes": " he is",

" howd": " how did",

" howdy": " how do you",

" howll": " how will",

" hows": " how is",

" id": " i would",

" ida": " i would have",

" im": " i am",

" ive": " i have",

" isnt": " is not",

" itd": " it had",

" itll": " it will",

" its": " it is",

" lets": " let us",

" maam": " madam",

" mightve": " might have",

" mighta": " might have",

" mightnt": " might not",

" mustve": " must have",

" musta": " must have",

" mustnt": " must not",

" neednt": " need not",

" oclock": " of the clock",

" shes": " she is",

" shoulda": " should have",

" shouldve": " should have",

" shouldnt": " should not",

" so'd": " so did",

" thatd": " that would",

" thats": " that is",

" thered": " there had",

" theres": " there is",

" theyd": " they would",

" theyda": " they would have",

" theyll": " they will",

" theyre": " they are",

" theyve": " they have",

" wasnt": " was not",

" weve": " we have",

" werent": " were not",

" whatll": " what will",

" whatllve": " what will have",

" whatre": " what are",

" whats": " what is",

" whatve": " what have",

" whens": " when is",

" whenve": " when have",

" whered": " where did",

" whers": " where is",

" whereve": " where have",

" wholl": " who will",

" whollve": " who will have",

" whos": " who is",

" whove": " who have",

" whys": " why is",

" whyve": " why have",

" willve": " will have",

" wont": " will not",

" wontve": " will not have",

" wouldve": " would have",

" wouldnt": " would not",

" wouldntve": " would not have",

" yall": " you all",

" yalls": " you alls",

" yalld": " you all would",

" yalldve": " you all would have",

" yallre": " you all are",

" yallve": " you all have",

" youd": " you had",

" youda": " you would have",

" youdve": " you would have",

" youll": " you you will",

" youllve": " you you will have",

" youre": " you are",

" youve": " you have",

" ain't": " are not",

" aren't": " are not",

" can't": " can not",

" can't've": " can not have",

" 'cause": " because",

" bc": " because",

" b/c": " because",

" could've": " could have",

" couldn't": " could not",

" couldn't've": " could not have",

" didn't": " did not",

" doesn't": " does not",

" don't": " do not",

" hadn't": " had not",

" hadn't've": " had not have",

" hasn't": " has not",

" haven't": " have not",

" he'd": " he would",

" he'd've": " he would have",

" he'll": " he will",

" he'll've": " he will have",

" he's": " he is",

" how'd": " how did",

" how'd'y": " how do you",

" how'll": " how will",

" how's": " how is",

" i'd": " i would",

" i'd've": " i would have",

" i'll": " i will",

" i'll've": " i will have",

" i'm": " i am",

" i've": " i have",

" isn't": " is not",

" it'd": " it had",

" it'd've": " it would have",

" it'll": " it will",

" it'll've": " it will have",

" it's": " it is",

" let's": " let us",

" ma'am": " madam",

" mayn't": " may not",

" might've": " might have",

" mightn't": " might not",

" mightn't've": " might not have",

" must've": " must have",

" mustn't": " must not",

" mustn't've": " must not have",

" needn't": " need not",

" needn't've": " need not have",

" o'clock": " of the clock",

" oughtn't": " ought not",

" oughtn't've": " ought not have",

" shan't": " shall not",

" sha'n't": " shall not",

" shan't've": " shall not have",

" she'd": " she would",

" she'd've": " she would have",

" she'll": " she will",

" she'll've": " she will have",

" she's": " she is",

" should've": " should have",

" shouldn't": " should not",

" shouldn't've": " should not have",

" so've": " so have",

" so's": " so is",

" that'd": " that would",

" that'd've": " that would have",

" that's": " that is",

" there'd": " there had",

" there'd've": " there would have",

" there's": " there is",

" they'd": " they would",

" they'd've": " they would have",

" they'll": " they will",

" they'll've": " they will have",

" they're": " they are",

" they've": " they have",

" to've": " to have",

" wasn't": " was not",

" we'd": " we had",

" we'd've": " we would have",

" we'll": " we will",

" we'll've": " we will have",

" we're": " we are",

" we've": " we have",

" weren't": " were not",

" what'll": " what will",

" what'll've": " what will have",

" what're": " what are",

" what's": " what is",

" what've": " what have",

" when's": " when is",

" when've": " when have",

" where'd": " where did",

" where's": " where is",

" where've": " where have",

" who'll": " who will",

" who'll've": " who will have",

" who's": " who is",

" who've": " who have",

" why's": " why is",

" why've": " why have",

" will've": " will have",

" won't": " will not",

" won't've": " will not have",

" would've": " would have",

" wouldn't": " would not",

" wouldn't've": " would not have",

" y'all": " you all",

" y'alls": " you alls",

" y'all'd": " you all would",

" y'all'd've": " you all would have",

" y'all're": " you all are",

" y'all've": " you all have",

" you'd": " you had",

" you'da": " you would have",

" you'd've": " you would have",

" you'll": " you you will",

" you'll've": " you you will have",

" you're": " you are",

" you've": " you have",

" hwy": " highway",

" fvck": " fuck",

" im": " i am",

" rt": " retweet",

" fyi": " for your information",

" omw": " on my way",

" 1st": " first",

" 2nd": " second",

" 3rd": " third",

" 4th": " fourth",

" u ": " you ",

" r ": " are ",

}

def expand_contractions(text, c_re=c_re):

c_re = re.compile('|'.join('(%s)' % k for k in contractions_dict.keys()))

def replace(match):

expansion = f" {contractions_dict[match.group(0)]}"

return expansion

text = c_re.sub(replace, text.lower())

return text

# function to expand contractions, remove urls and characters before tokenization processing

def denoise_text(text):

new_text = re.sub(r"\S*https?:\S*", r"", text.lower())

new_text_contractions = expand_contractions(new_text)

new_text_punct = re.sub(r"[^\w\s@#]", r"", new_text_contractions)

new_text_ascii = re.sub('[^\u0000-\u007f]', '', new_text_punct)

strip_text = new_text_ascii.strip()

text = re.sub('#\w+', '', strip_text)

return text

# tokenization & lemmatization function returns tokens

def lemmatize_text(text):

tokenizer = TweetTokenizer(strip_handles=True, reduce_len=True)

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

return [lemmatizer.lemmatize(w, pos='v') for w in tokenizer.tokenize(text)]

# tokenization & stemmer function returns tokens

def stem_text(text):

tokenizer = TweetTokenizer(strip_handles=True, reduce_len=True)

stemmer = PorterStemmer()

return [stemmer.stem(w) for w in tokenizer.tokenize(text)]

def replace_numbers(tokens):

# replace integers with string formatted words for numbers

dig2word = inflect.engine()

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

if word.isdigit():

new_word = dig2word.number_to_words(word)

new_tokens.append(new_word)

else:

new_tokens.append(word)

return new_tokens

def remove_non_ascii(tokens):

# remove non ascii characters from text

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

new_token = unicodedata.normalize('NFKD', word).encode('ascii', 'ignore').decode('utf-8', 'ignore')

new_tokens.append(new_token)

return new_tokens

# remove stopwords

def remove_stopwords(tokens):

stop_list = stopwords.words('english')

new_tokens = []

for word in tokens:

if word not in stop_list:

new_tokens.append(word)

return new_tokens

def norm_text(tokens):

words = replace_numbers(tokens)

tokens = remove_stopwords(words)

return tokens

def process_text(text):

clean_text = denoise_text(text)

lem_text = lemmatize_text(clean_text)

text = ' '.join([x for x in norm_text(lem_text)])

text = re.sub(r"-", r" ", text)

return text

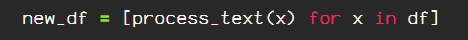

new_df = [process_text(x) for x in df]

return new_df

To process the text:

df['tweets'] = tweet_preprocess(df.text)

This is just the initial preprocessing of the tweets to clean up the text noise and extras that aren’t needed and will end up convoluting the data when modelling.