An OpenCV tutorial in Python

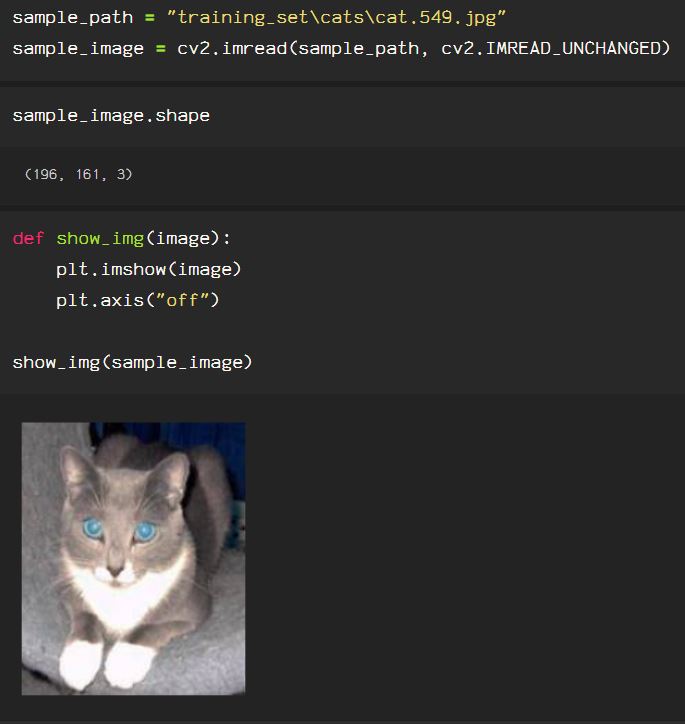

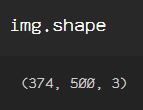

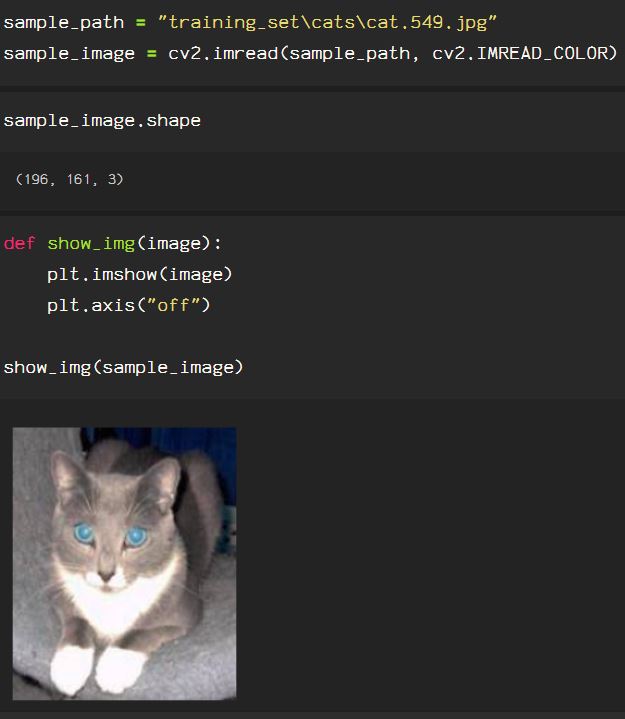

Previously, I discussed color spaces and processes used to enhance or restore images. In most real world scenarios, data is rarely perfect, and that goes for images as well. Whether it’s lighting, pixelation or some other visual anomoly, these instances must be accounted for in the preprocessing stages. I will, once again, be using images from the Kaggle dataset of cat & dog images found here.

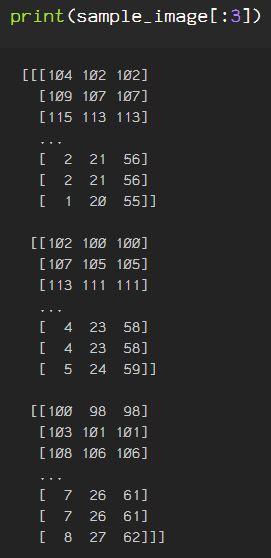

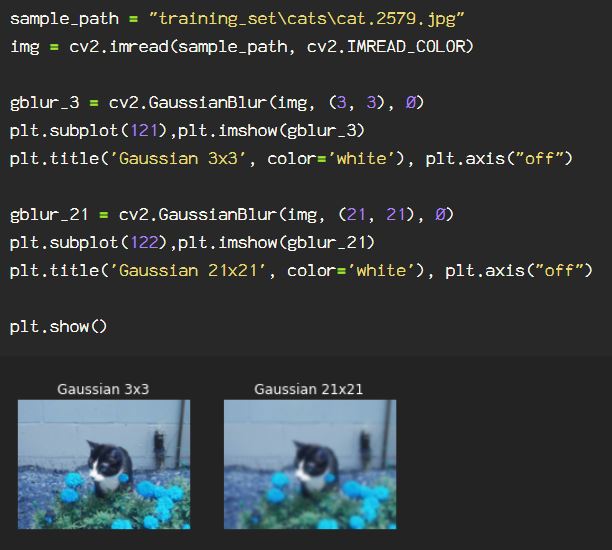

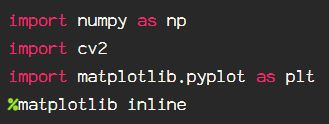

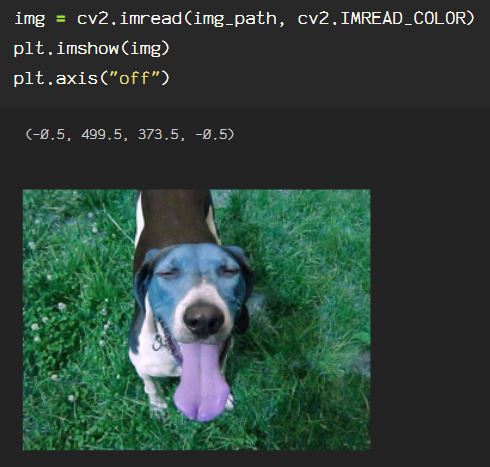

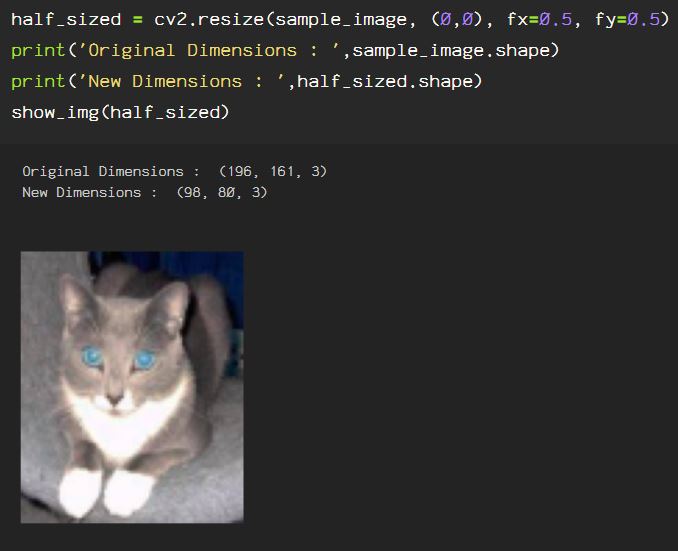

The first option is a simple Gaussian blur, which will provide normally distributed data in images as well. Start by importing and reading the image into an OpenCV Mat with cv2.imread().

Next, apply the function cv2.GaussianBlur() to the image, including the size of the kernel. The larger the kernel, the blurrier the image, followed by the standard deviation in X direction, or sigmaX, which is used for the sigmaY parameter when not defined.

As seen when the code runs, the larger kernel is significantly blurrier, as expected.

Another quick blurring option is the median blur, which when applied, finds the median value at the neighborhood of each pixel.

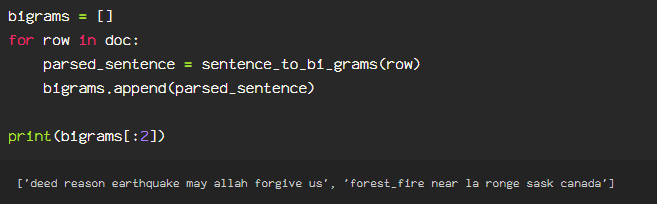

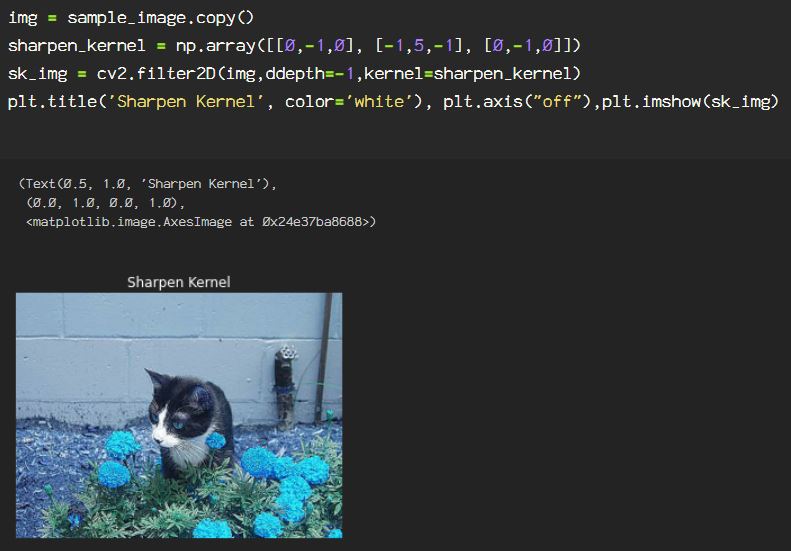

If you’re hungry for the option of having more control over the kernels applied, then we can always create our own kernels using Numpy.

The kernel is also called a filter in this application, due to the fact that it serves as a sort of lens for each pixel, the anchor pixel is the center pixel, when the kernel is over the image, pixel by pixel, it slides across, and as the product is summed for the surrounding kernels, the anchor kernel value changes, and is applied to a ‘copy’ of the original, with alterations for each pixel dictated by the kernel. The values in the kernel are multiplied by the pixel value it is over, then all of those values are summed to get the anchor’s new value.

Here, the kernel created is for sharpening the image, and I am using a 3×3 kernel for this process. To apply the kernel to the image, the function cv2.filter2D() is used, the ddepth parameter is set to -1 to keep the image format the same as the source, and lastly, the kernel used is the sharpen_kernel created as a numpy array.

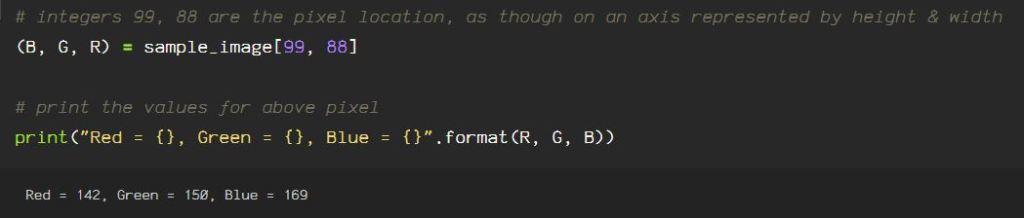

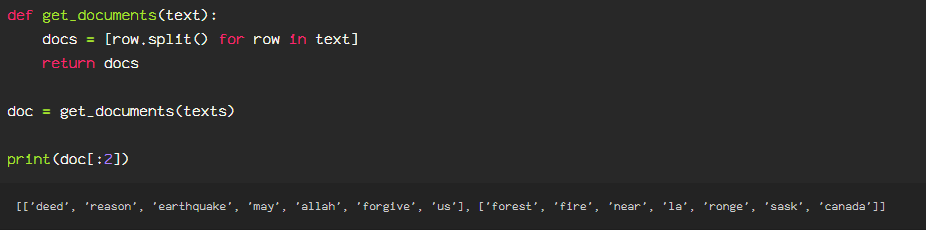

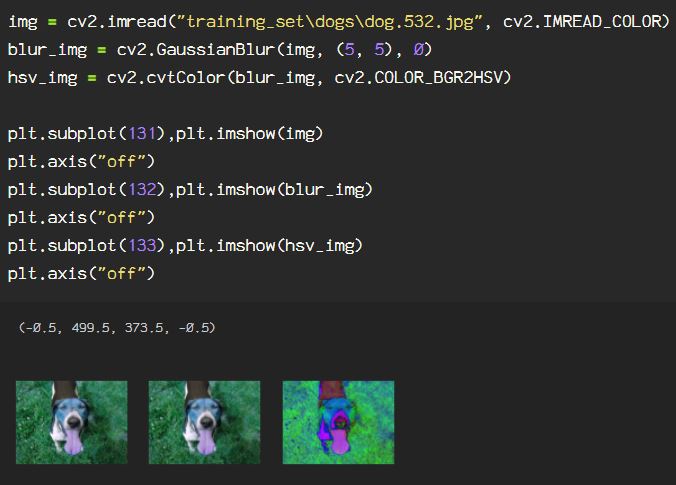

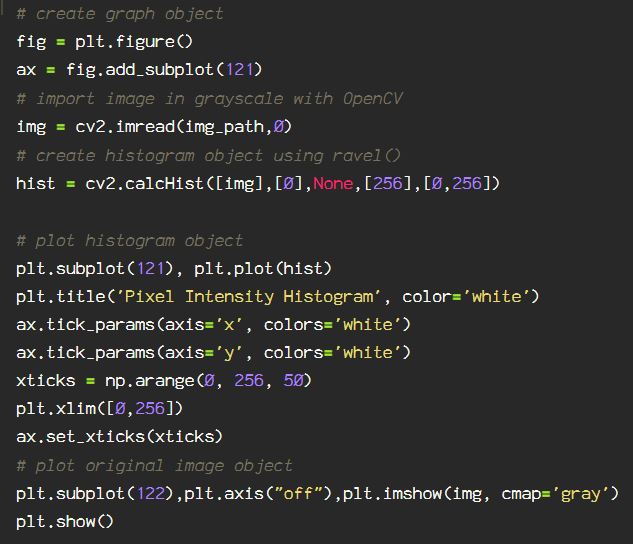

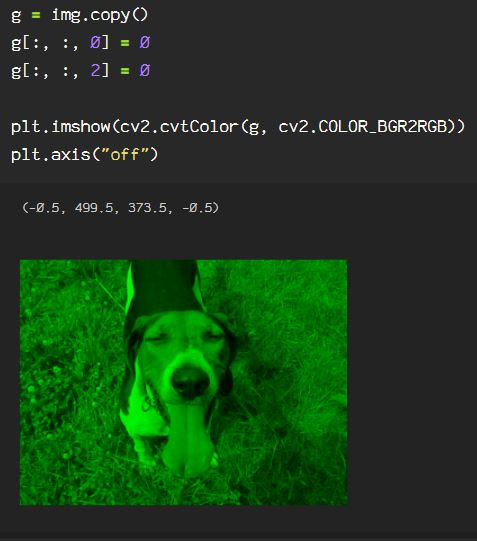

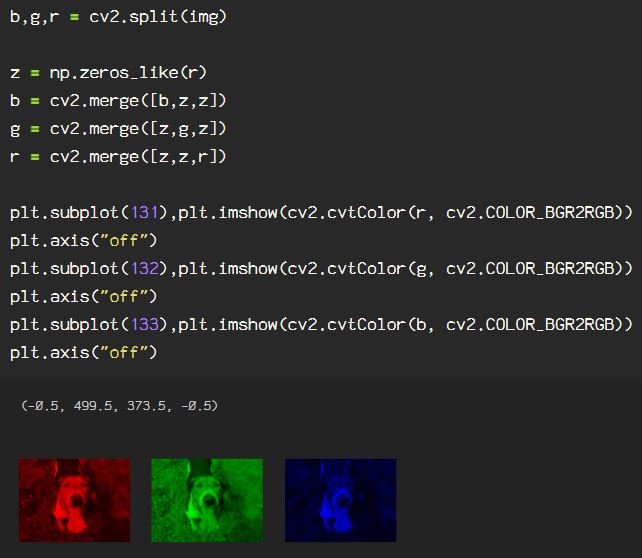

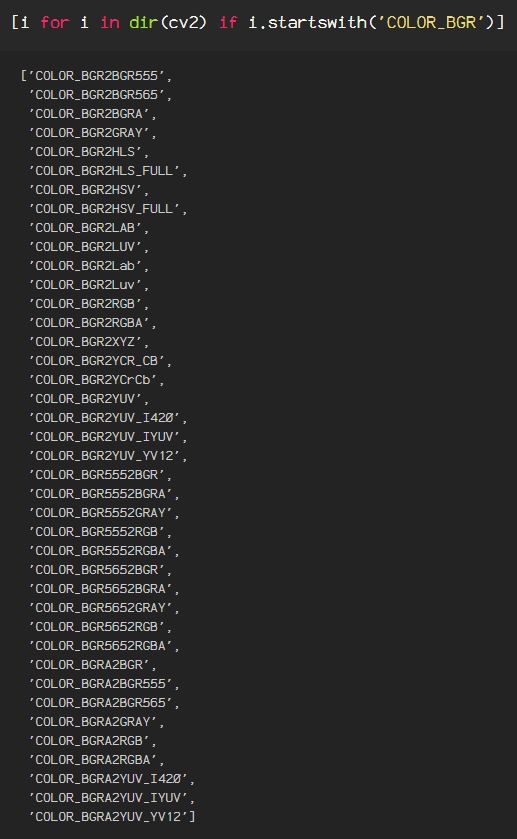

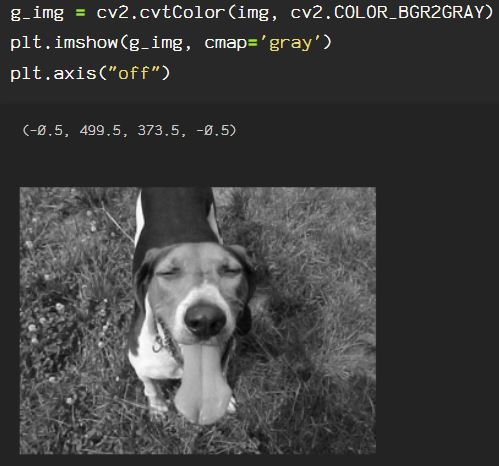

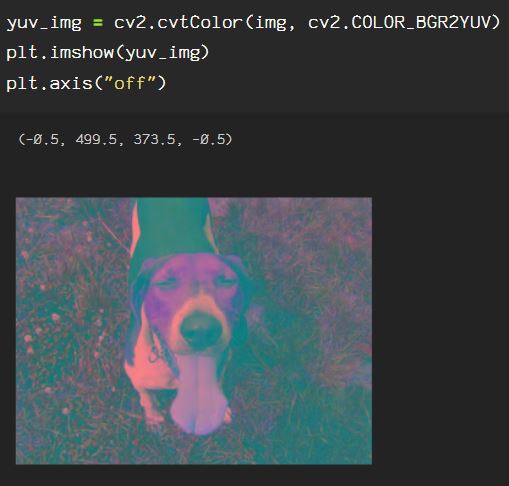

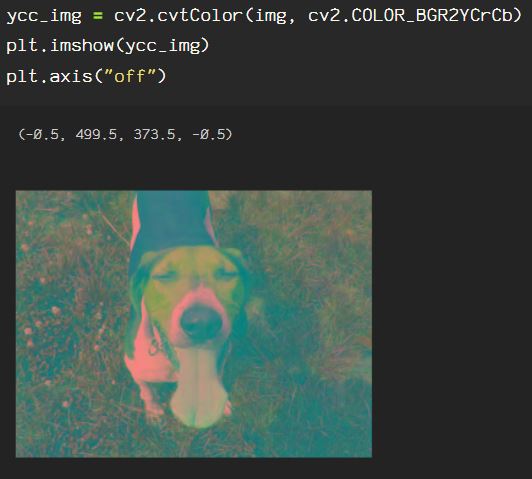

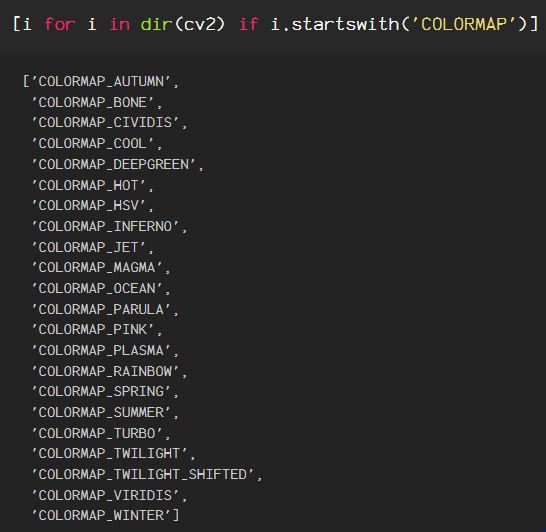

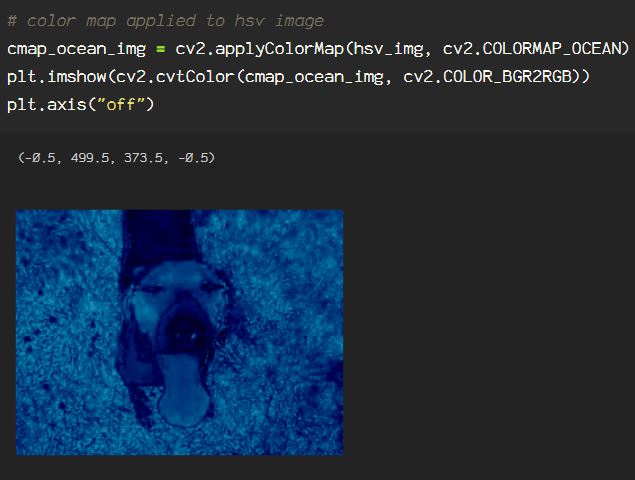

Now, say we want to get rid of extraneous information in the image, say I only want the subject from the image. Here, I will go through the process of creating an image mask. Start by reading the image in BGR, then convert it to an HSV color space. If you need a review of color spaces, check out my previous blog on OpenCV color spaces.

Let’s start by reading the image, then applying a Gaussian blur, followed by converting to the HSV color space.

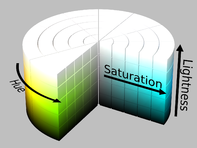

I will be applying thresholds to the hue, saturation and value attributes to create the mask. The way HSV color space translates the standard primary colors is as follows:

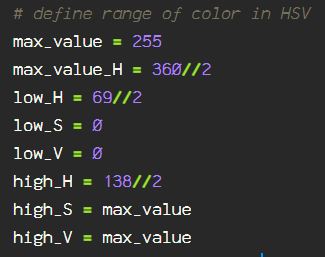

The hue is based on the color wheel, with 360 degrees of color, but that’s over 255, which is the space in which we are working with our hue in images.

In order to remain in the standard 255 range, the limit of the 8-bit image color data points, I am dividing the hue information using floor division to remain within the limit.

Now that I have the low and high values for each, I use the cv2.inRange() function to my hsv_img. Then, because the mask is actually masking everything EXCEPT for the green shades, I use the cv2.bitwise_not() function to the mask threshold image. To show the masked image, and the inverse masked image, I am using the cv2.bitwise_and() function. To get more information on the arithmetic operations check out the OpenCV documentation here. The duplicate hsv_img parameter is simply due to the fact that I am doing operations only on this image. The arithmetic process can be used for blending images, in which case, there would be a second source rather than the duplicate source I am using here.

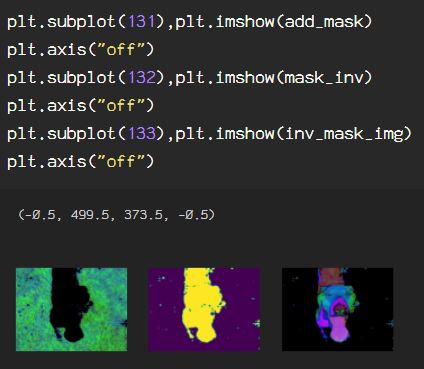

Now, here is what each stage of the process looks like:

The first image is the mask created using the threshold ranges using bitwise_and(). The next image is the inverted mask, created with bitwise_not(). The third is the image with the inverted mask thresholds applied to the image, blending with a second copy of the image.

Our image is still in the HSV color space though, so to see what the image looks like in standard RGB color space, simply convert from the HSV color space to RGB.

This can be finessed by initializing this process with custom kernels for the blurring process, and altering the threshold range for the image. I focused on the green in the image since there is predominantly green in the background of the image. To focus on other shades or colors, when using the cv2.inRange() function, you may have to filter the image twice, since the colors you may want to focus on are not necessarily next to each other on the HSV color wheel.

![RGB vs BGR Subpixel Layout - What's The Difference? [Simple]](https://www.displayninja.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/RGB-vs-BGR-Subpixel-Layout-1200x900.jpg)